I’ve just finished reading a recently published, forcefully critical look at the progress of queer theory:

If Memory Serves: Gay Men, AIDS, and the Promise of the Queer Past (Christopher Castiglia and Christopher Reed, University of Minnesota Press, 2012). It questions the ways that some very influential work in the field has deemphasized history and memory in our understanding of gay culture. I won’t here get into an elaborate summary of its academic arguments.

But the key point of the book has really gotten under my skin: the authors’ claim that we’ve developed collective amnesia about the AIDS crisis, a post-traumatic refusal to remember. We not only fail to remember the crisis. We’ve forgotten along with the crisis the strength of the culture that an LGBTQ coalition built to respond to it. And even more profoundly, we’ve repudiated the sexual revolution that built post-Stonewall gay culture in the first place. But the authors aren’t just lamenting the loss of a past that’s over and done with. More importantly, in forgetting the past, we’ve also cut ourselves off from precious resources for imagining and living toward a queer future. In our amnesiac flight from mourning, we’ve also fled what they call “the promise of the queer past.”

Maybe their argument hit me so deeply because I’m 56 and just spent three weeks in San Francisco, my first extended stay there since a hip replacement told me forcefully a couple of years ago that my life’s not the same as it used to be. If you need cheering up, this post isn’t for you. I’m going to begin with grief. And I claim the right of the drama queen to take you on a tour of my

lieux de mémoire.

This trip to San Francisco, I stayed in an apartment a five-minute walk from the bed-and-breakfast I settled into in September 1986. I took my first walk along Castro Street in the company of a younger friend with whom I’d flown up the coast from San Diego. The street was thick with the likes of us.

Ten minutes’ walk in the other direction, somewhere south of Market along Duboce stands the building where I first met the gentle, intelligent, gifted man my young friend had just fallen in love with, six months later when he was newly moved to the city.

Back around the corner from Castro on 19th, in a house whose address I've also forgotten, is the apartment into which they later moved, where from visit to visit I witnessed, as in time-lapse photography, the progressive deterioration of my friend’s lover, diagnosed very soon after they'd found each other. T. would stay with him to the end; he took to kissing his beloved’s KS lesions as they lay together evenings on the couch. Meanwhile, he’d find sexual recreation at Blow Buddies, reassured that everything he indulged in there fell within current safety guidelines; and would subsequently sero-convert as a result of those safe(r) excursions, an exception to the harm-reduction rule.

Just north of Market, across Church Street from the Safeway, stands St. Francis Lutheran, which I wrote about earlier this month. I’ll quote these lines from that post: “I first walked into St. Francis in 2000…. As the Gospel book was carried in a very short procession into the middle of the congregation, everyone turned to face the reader… and then crowded from the pews into the central aisle, hands laid on shoulders in a web that knit the whole assembly into a single body with a living voice at its center. And I lost it.”

Inbound on Market Street, for a scant decade beginning in the mid-80’s, a black door opened onto a safe-sex space known simply by its address as the 1808 Club. It offered clear rules of engagement (lips above hips, and not even the appearance of penetration) that headed off the awkwardness of negotiating limits with prospective partners; ample lube and paper towels everywhere one turned; a series of spaces that flowed easily and invitingly into one another, allowing for cordial connections and cordial disengagements, but giving little opportunity to hive off into pairs or groups impervious to others as they passed by.

Camaraderie prevailed; and sometimes blossomed into something for which camaraderie is an inadequate label: a liminal state in which mutual desire and the gifting of pleasure offered something more--a time and space for meeting the Other, a recognition of the Other’s intrinsic and irreplaceable worth, an affirmation of the self in relation to that Other—an opening into a relation of I/Thou; a performed faith that the transcendent dwelt in one’s own flesh and in the flesh of those one touched. (Here too, as at St Francis Lutheran, at the best of times, an assembly was knit together into a single body with a living voice at its center. And I lost it.)

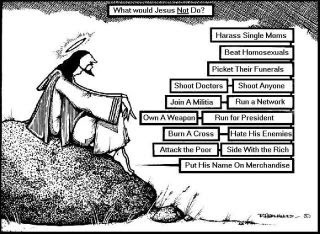

Maybe I'm just letting advancing age get the better of me, but it’s hard for me not to say, as I wander through these sites of memory, it’s so over. We wanted an army of lovers, and we’re preparing to settle for the right to marry, seduced by the very opposition that still vociferously contests that self-evidently domesticated and hardly revolutionary goal. We wanted an army of lovers, and we settled for the right to bear arms in service of a country whose foreign policy has successfully combined brutal imperialism with spectacular fecklessness. We wanted a world of playful, positive, joyful, healing sexuality, and instead we got ManHunt and Grinder. We wanted ecstasy, and instead we got Ecstasy.

What I feel now isn’t the grief of a man who spent ten years watching his friends and lovers die around him, and sometimes in his arms: for the most part, I inhabited the hinterlands of the health crisis, and if anything, I carry a half-suppressed guilt for the fact that I remained so insulated from the depths of raw personal loss. Instead, I feel grief for the world that those who died longed to build—mixed with guilt that I failed to risk more, when I had the chance, to build it with them.

They were aiming for a world, as Judith Butler puts it in

Undoing Gender, in which we’re undone by each other—and if not, as she goes on to ask, what’s the point? They sustained themselves on possibility, if we remember how partial and momentary that world's inbreaking remained—for, to paraphrase Butler once again, possibility isn’t a luxury, but as crucial as bread.

To move from abstracted and not very sexy language back to my places of memory, to be clearer about what I’m trying to work out here, these are a few moments of Grace: my friend Tom kissing the KS lesions of his dying beloved; the ashes of several dozen men who (whatever else one might or might not know of them) had probably lived lives to enrage the religious right, lovingly and reverently placed below inscribed paving stones in the garden of a small Lutheran church; the whimpering gratitude of a man surrounded by a knot of more or less anonymous jackoff enthusiasts. They’re moments of Grace not because they speak to some essential core of human nature, or somehow express a deep truth of what human sexuality is intended to be, but because they were a response to emergent possibility as we chose to be undone and remade in relation to one another.

If you share any part of this grief for your own fragments of the queer past, we share the recognition that we’ve lost a web of connections. Butler would also remind us that to grieve is to acknowledge that we’ve been touched, and in the experience of being touched been transformed and thrown off center by the presence of the other.

I long now for that decenteredness: for the sense that, whatever our lives meant, the promise they held out had to do with what they meant and might come to mean together--that we were, indeed, in Butler’s sense, undone by one another, thrown off center, left not the same and not complete within ourselves. I long for the crowding together of the whole congregation into a single body—whether to hear the Gospel in the midst of Mass, or to hear the equally good news of the sanctity of flesh proclaimed by half a dozen men sheltering a comrade through his experience of ecstasy. The memory of T.’s brave, edgy experimentation--supporting his lover through terminal illness and at the same time taking affirmative responsibility for the cultivation of his erotic self--seems a fragment of a world of vanished possibility, lost as we’ve rushed to reassure that most tyrannical of addressees, the Undecided Moderate, that we want nothing more and nothing other than what s/he would want—marriage, military service, ordination—if s/he hadn’t had it all the time.

And yet—I don’t view grief for that world as a negative experience. I wouldn’t anaesthetize myself if I could. Memory goes hand in hand with desire, and desire points not just toward the past, but (as Castiglia and Reed point out) toward a future we can only partly imagine. What I’m asking myself now, more than anything else, is, how do I, how do we, lay claim to a future that’s worthy of the brave, loopy, risk-embracing past, the past that includes Walt Whitman and Edward Carpenter, includes Magnus Hirschfeld and Allen Ginsberg and James Baldwin and Harry Hay and Thom Gunn and Keith Haring and Michael Callen?